Scientists from the University of Maryland have made a significant discovery regarding moonquakes, revealing that these seismic events, rather than meteoroid impacts, are responsible for terrain shifts near the Apollo 17 landing site. The study, published on December 7, 2025, indicates that an active fault has generated these quakes over millions of years, prompting a reevaluation of future lunar mission planning.

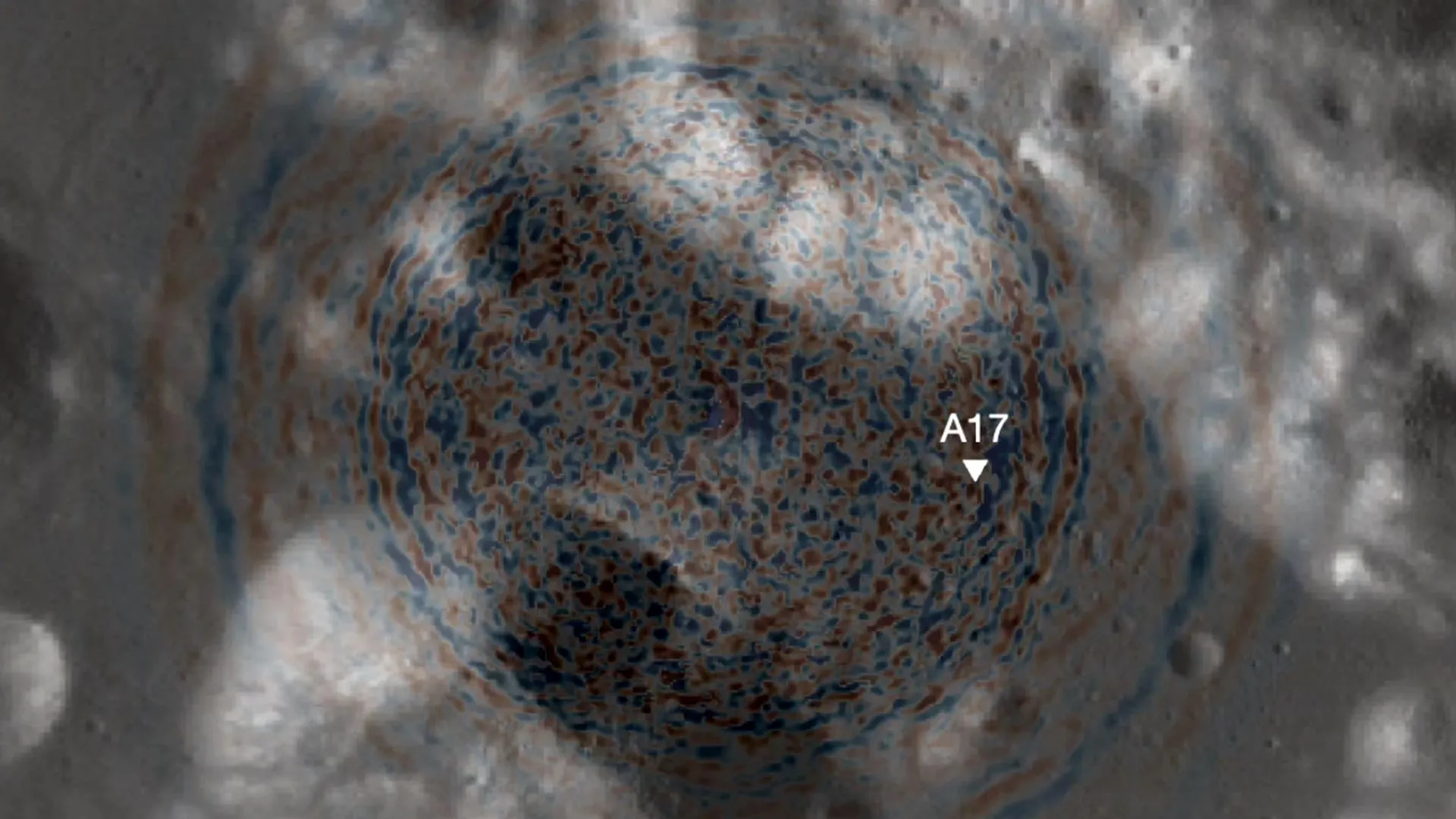

The findings stem from a detailed analysis of the Taurus-Littrow Valley, where the Apollo 17 astronauts landed in 1972. Researchers, including Thomas R. Watters, a Senior Scientist Emeritus at the Smithsonian, and Nicholas Schmerr, an Associate Professor of Geology at the University of Maryland, assessed geological samples and observations made during the mission. They found that moonquakes triggered boulder movements and landslides, leading to a better understanding of the seismic activity in the region.

To estimate the intensity of past moonquakes, the researchers analyzed geological evidence such as boulder falls and landslides. “We don’t have the sort of strong motion instruments that can measure seismic activity on the moon like we do on Earth, so we had to look for other ways to evaluate how much ground motion there may have been,” Schmerr stated.

Active Faults and Future Risks

The study suggests that moonquakes with magnitudes near 3.0 have repeatedly affected the area over the past 90 million years. These seismic events are linked to the Lee-Lincoln fault, a tectonic feature running through the valley floor. The research indicates that this fault is still active and could generate new seismic activity.

Watters emphasized the implications of their findings for future lunar operations, stating, “The global distribution of young thrust faults like the Lee-Lincoln fault… should be considered when planning the location and assessing stability of permanent outposts on the moon.”

The researchers calculated the risk of a damaging quake occurring near an active fault, estimating a one in 20 million chance on any given day. While this may sound minimal, they noted that the risk increases significantly for long-term missions. “If you have a habitat or crewed mission up on the moon for a whole decade, that’s 3,650 days times one in 20 million, or the risk of a hazardous moonquake becoming about one in 5,500,” Schmerr explained.

Implications for NASA’s Artemis Program

Upcoming missions, including those involved in NASA’s Artemis program, which aims to establish a continuous human presence on the moon, will need to consider these risks carefully. The Artemis program plans to deploy more advanced technologies than those used during the Apollo missions, including improved seismic instruments.

Watters and Schmerr urged future lunar planners to avoid constructing facilities directly on or near scarps and active faults. “The farther away from a scarp, the lesser the hazard,” Schmerr advised.

This research has been supported by data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been operational since June 18, 2009. The LRO mission has provided crucial imaging and topographical data that contribute to understanding lunar geology.

In summary, the discovery of moonquake activity near the Apollo 17 site has important implications for the planning of future missions and long-term lunar habitation. As scientists continue to study the moon’s seismic history, they aim to ensure that exploration efforts are conducted safely and effectively.