Research conducted by astrophysicist Ryo Sawada and colleagues suggests that cosmic rays from supernova explosions may play a critical role in the formation of Earth-like planets. Published on December 21, 2025, in the journal Science Advances, this study shifts the understanding of how early solar systems may have developed, particularly in relation to the formation of rocky planets like Earth.

For decades, scientists believed that short-lived radioactive elements, such as aluminum-26, were introduced into the early solar system by nearby supernovae. These elements were thought to be essential in shaping rocky planets, as their decay generated heat that depleted water and other volatile materials from young planetesimals. However, the traditional “injection” theory hinged on the rare occurrence of a supernova exploding at just the right distance—a scenario that seemed unlikely.

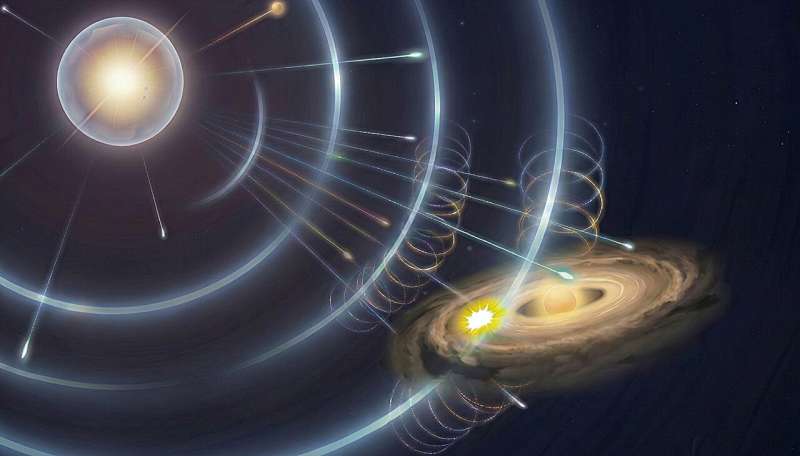

In his exploration of supernova physics, Sawada began to question the completeness of this explanation. He noted that supernovae are not merely explosive events but also serve as powerful particle accelerators, generating vast quantities of high-energy particles known as cosmic rays. These cosmic rays, he posited, could significantly influence the composition of the protosolar disk.

By employing numerical simulations, the research team investigated the interactions between cosmic rays and the protosolar disk. Their findings revealed that cosmic rays could induce nuclear reactions that generate short-lived radioactive elements like aluminum-26. Notably, the simulations indicated that these elements could be produced at distances of around one parsec from a supernova, a distance commonly found in star clusters. This distance allows the protosolar disk to remain intact, eliminating the need for a serendipitous injection event.

Sawada and his team propose this mechanism as a “cosmic-ray bath,” a process that could be far more universal than previously thought. Many sun-like stars are born in clusters, often alongside massive stars that eventually undergo supernova explosions. If cosmic-ray baths are prevalent in such environments, the conditions conducive to creating Earth-like planets could be much more common than once believed.

The implications of this research extend beyond the formation of planets. If Earth-like planets do not require the rare occurrence of a supernova encounter, it opens up possibilities for similar rocky planets to exist around a larger number of sun-like stars. This suggests that the thermal histories that shaped Earth’s interior might not be as unique as previously thought.

Despite these encouraging findings, Sawada emphasizes that the presence of cosmic rays alone does not guarantee the formation of habitable planets. Factors such as disk lifetime, cluster structure, and stellar dynamics still play crucial roles in planetary development. This research highlights the interconnections between high-energy astrophysics and planetary science, reflecting how complex astrophysical processes can shed light on questions about habitability.

This study serves as a reminder that the key to understanding the origins of Earth-like planets may lie not in complicating existing theories but in recognizing overlooked aspects of cosmic phenomena. The research represents a significant advancement in the field, suggesting that the conditions necessary for forming rocky planets could be more prevalent in the universe than previously assumed.

For further insights into the latest developments in science and astrophysics, readers can stay informed through reputable sources like Science Advances and other scientific publications.