During mating season, male white-tailed deer engage in behaviors designed to attract females and deter competitors. They rub their antlers against trees, scrape the forest floor, and subsequently urinate on these marked areas. A recent study published in the journal Ecology and Evolution reveals that these physical and scent markers possess an additional, surprising feature: they also emit a glow, making them visible to other deer in the dark.

Researchers from the University of Georgia conducted a detailed investigation into these behaviors, uncovering a complex visual language that extends beyond mere scent. The study highlights the importance of these glowing markers, particularly during the low-light conditions typical of dawn and dusk when deer are most active.

Understanding the Glow

The phenomenon occurs due to the interaction of urine with the natural environment, particularly when it is deposited on specific surfaces. The study found that the urine of male deer glows under ultraviolet light, a characteristic that is undetectable to humans but plays a crucial role in deer communication. This glowing effect serves as a visual signal, enhancing the visibility of scent markings to other deer, facilitating both mating and territorial behaviors.

The researchers observed that during the mating season, male white-tailed deer are particularly active in marking their territory. By rubbing their antlers and urinating on trees and the forest floor, they create a vivid display intended to catch the attention of potential mates and assert dominance over rival males. The glowing urine acts as a “beacon,” guiding other deer to these important locations.

Implications for Wildlife Behavior

The findings of this study have significant implications for understanding the communication strategies of deer and potentially other wildlife species. The ability to signal visually in addition to chemically opens new avenues for research into animal behavior and ecology. It suggests that many species may utilize similar methods of communication that remain unnoticed by human observers.

This research not only sheds light on the complexities of deer interactions but also emphasizes the need for ongoing studies into the sensory modalities used by animals in their natural habitats. The glow of urine in deer could represent just one facet of a broader, intricate language that exists within the animal kingdom.

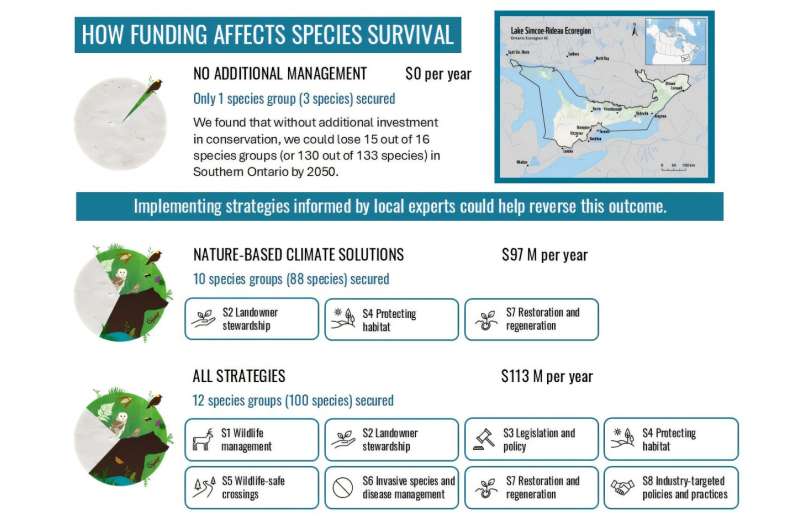

As scientists continue to explore these behaviors, the insights gained may enhance conservation strategies and inform wildlife management practices. Understanding how animals communicate and interact with their environment is crucial for preserving biodiversity and maintaining healthy ecosystems.

In conclusion, the discovery of glowing urine in male white-tailed deer represents a fascinating intersection of behavior, ecology, and communication. As researchers delve deeper into this phenomenon, they may uncover even more secrets about the remarkable ways in which animals navigate their world.