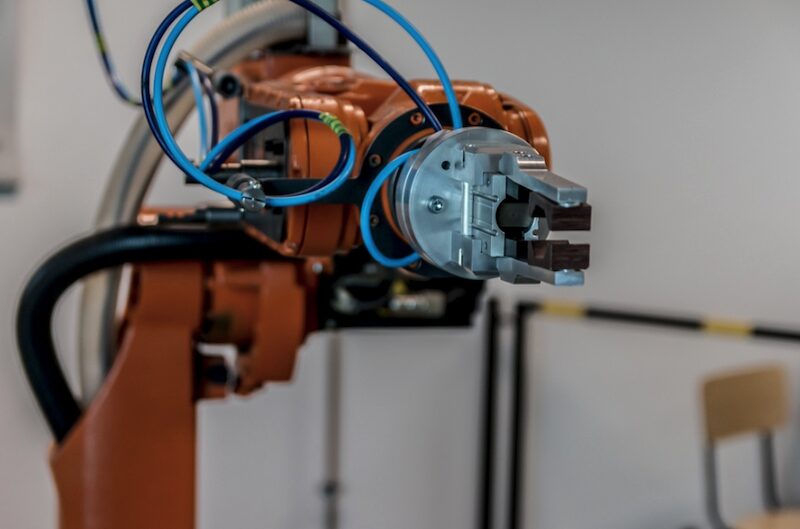

The integration of robotics and smart controls in manufacturing has transformed production processes, yet the importance of tool geometry remains essential. As robots handle parts and CNC machines adapt production parameters in real time, the interaction between the cutting tool and the material is where the real action occurs. Tool geometry, comprising elements such as helix angles and edge preparation, determines the effectiveness of these advanced systems.

Why Tool Geometry Is Still Crucial

Despite advancements in technology, the basic physics of chip formation has not changed. Factors like rake angles, flute counts, and corner geometry continue to dictate cutting forces, heat generation, and chip flow. If the selection of these components is flawed, even the most sophisticated “smart” systems will struggle to maintain a stable and productive cut. In this context, the choice of end mill can significantly impact outcomes, particularly when maintaining unattended robotic operations.

Research initiatives, including those at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), highlight the importance of pairing robotics with appropriate cutting tools. These studies examine how artificial intelligence (AI) and sensors can enhance machining conditions in real time, but they inherently rely on the assumption that the cutting tools are suitable for the task at hand. AI-driven analytics can optimize established processes but cannot rectify the issues stemming from poor geometry decisions.

The Interplay of Geometry and Robotics

In a typical high-mix job shop, robots may be tasked with machining diverse materials, from stainless steel brackets in the morning to aluminum housings in the afternoon. While CNC parameters can be programmed to change with each job, the geometry of the tools often dictates the success of these operations. Research indicates that minor adjustments in edge radius, rake angle, and helix angle can lead to significant alterations in cutting forces and surface finish, underscoring the sensitivity of these parameters.

A recent study on machining quality found that optimizing tool micro-geometry could reduce cutting forces and improve surface roughness, enhancing consistency and tool life across multiple parts. This suggests that treating tools merely as items on a purchase order overlooks critical aspects of their performance. For instance, a high-helix, polished three-flute end mill may prove more effective in aluminum machining than a four-flute general-purpose tool, which could lead to operational inefficiencies and increased downtime.

When robots are introduced into the production environment, maintaining process robustness becomes paramount. Unlike human operators, who can detect issues through auditory cues, robots will continue to operate until a failure occurs. Tool geometry acts as a safeguard against such silent failures. For example, a small corner radius can relieve stress at the tool tip during the machining of hard stainless steel, thereby extending tool life and minimizing dimensional drift.

In applications where chip evacuation is crucial, selecting a tool with appropriate flute count and chip space can determine success. A two- or three-flute design may facilitate effective chip clearance in tight pockets, while a four-flute tool with limited chip space may generate excess heat, leading to chatter and inefficiencies. In these scenarios, robots will not adjust for geometry flaws; they will simply reveal the consequences of those choices.

Strategies for Optimizing Tool Geometry

As manufacturers invest in smart CNC and robotic systems, it is vital to formalize tool geometry decisions. One approach is to standardize tool families based on material and operation rather than merely diameter. For example, specifying high-helix, polished three-flute tools for aluminum and low-helix, multi-flute designs for hard steels can optimize performance.

Moreover, integrating geometry considerations into the process approval workflow is essential. When new parts are introduced into robotic cells, evaluating not only feeds and speeds but also helix angles, flute counts, and corner geometries is critical. Simple questions can guide these decisions: Will the flute configuration effectively clear chips? Is the corner design robust enough for the intended engagement? Does the edge preparation align with material and coolant strategies?

Gathering data on tool performance and feeding that information back into standard practices will gradually build a library of geometries that support automated operations. Tools that consistently yield better surface finishes or fewer overload alarms should be treated as benchmarks for future projects.

In conclusion, while smart CNC controls and industrial robots enhance manufacturing capabilities, the foundation of a successful process remains rooted in tool geometry. By prioritizing geometry as a critical design decision, manufacturers can maximize the benefits of every sensor, robot, and algorithm implemented on the shop floor.