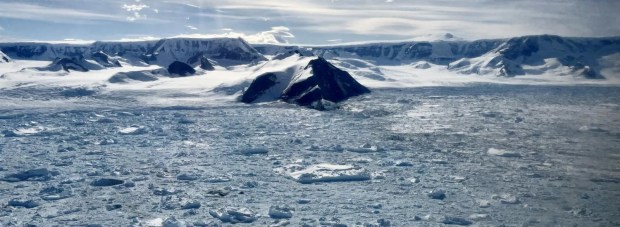

A team from the University of Colorado Boulder has revealed a significant discovery regarding the Hektoria Glacier in Antarctica, which experienced an unprecedented retreat, losing approximately half of its mass in just two months. This rapid decline occurred between January 2022 and March 2023, marking it as the fastest recorded retreat of a grounded glacier in history.

Research Affiliate Naomi Ochwat led the investigation after observing the glacier’s alarming rate of retreat during her monitoring of Antarctic glaciers. The Hektoria Glacier, which measures about 8 miles across and 20 miles long, retreated around 15.5 miles in this short timeframe. Ochwat sought to determine the underlying causes of this swift movement.

“This process, if replicated on larger glaciers, could have significant consequences for the overall ice sheet’s stability, leading to accelerated sea level rise,” Ochwat stated. Although the immediate impact of Hektoria’s retreat on global sea levels is minimal—amounting to fractions of a millimeter—scientists are particularly interested in the processes that led to this rapid change.

The glacier’s retreat was closely linked to the loss of fast ice, which supports the glacier’s floating ice tongue. As warmer temperatures caused this crucial layer of fast ice to break away, the glacier’s ice tongue began to disintegrate into the ocean. Ted Scambos, a Senior Research Scientist at CU Boulder, explained the mechanics involved. The glacier sits atop an ice plain, a flat area of bedrock below sea level. As warmer water thinned the glacier, the ice began to rise, allowing water to push underneath, leading to large ice slabs breaking off.

Scambos likened this calving process to a domino effect, where the retreat of one slab triggered further collapses. “The retreat of Hektoria and the loss of ice into the ocean is not unusual. What is critical, however, is the mechanism that causes rapid retreat,” he noted.

The study found that the primary driver of this retreat was the ice plain calving process rather than atmospheric or oceanic conditions. Using satellite-derived data, including images and elevation readings, the team was able to gain insights into the glacier’s behavior. This suggests that similar glaciers resting on ice plains may also be prone to destabilization.

Scientists highlighted that during the last glacial period, Antarctic glaciers with ice plains retreated at rates of hundreds of meters per day. This historical context has helped researchers understand the forces at play in Hektoria’s retreat, which Scambos emphasized as the fastest retreat for a grounded glacier ever documented.

The implications of these findings are significant. Ice sheets contain vast amounts of water, and their melting could lead to substantial increases in sea level. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, nearly 30% of the population in the United States resides in coastal areas vulnerable to flooding and erosion due to rising sea levels. Globally, eight of the ten largest cities are located near coastlines, as reported by the United Nations Atlas of the Oceans.

“What happens in Antarctica does not stay in Antarctica,” Ochwat remarked. “This research is vital as it uncovers processes that could have profound effects, not just for the ice sheets but for global communities.”

The ongoing study of Hektoria Glacier and other similar structures will be essential in assessing future risks and understanding the changing dynamics of ice sheets in Antarctica.