Charles C. Hofmann, an itinerant painter, transformed his challenging circumstances into a significant artistic legacy during the late 19th century. Arriving in New York from Germany in 1860, Hofmann eventually settled in Pennsylvania, where he became known as one of the three prominent almshouse painters. His works continue to capture the complex narratives of poverty and survival during a time when almshouses served as both refuge and last resort for the indigent.

The Historical Context of Almshouses in America

Almshouses have a long history in England, where they were established as charitable institutions to support the poor, sick, and vulnerable. This practice crossed the Atlantic with William Penn, who introduced the concept to North America. In Philadelphia, the Society of Friends constructed an almshouse as early as 1713. However, notable figures like Benjamin Franklin criticized these institutions, believing that merely providing aid perpetuated poverty. Franklin advocated for a system where residents could work in exchange for their keep, leading to a significant evolution in almshouse practices.

By 1825, Pennsylvania mandated counties to establish almshouses. These institutions evolved to include not just poorhouses but also workhouses, orphanages, asylums, and hospitals, reflecting a more comprehensive approach to social welfare. The Blockley Almshouse, which opened in West Philadelphia in 1835, later became known as Philadelphia General Hospital in 1919.

During the 19th century, many saw almshouses as a last resort. The homeless often sought shelter during harsh winters, where they were assigned work such as shoe repair, button making, or farming. These institutions provided basic necessities, but entering one meant sacrificing personal freedom, which many residents sought to escape when conditions improved.

Charles C. Hofmann: The Artist and His Journey

Within this landscape of hardship, Charles C. Hofmann emerged as a unique figure. Born in 1820, he painted his first work at the Berks County Almshouse in 1865, where he later became a regular resident. His life was marked by instability and struggles with alcoholism, which eventually led him to the poorhouse. Records indicate that he was admitted for “intemperance,” a reflection of the challenges he faced.

Hofmann spent much of his career along the Schuylkill River, working as an itinerant painter. Despite the advent of photography, which began to replace traditional portrait painting, Hofmann maintained his craft. He is known to have painted a total of 17 works related to almshouses, with several pieces displayed at prestigious institutions such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

His paintings are characterized by a naïve style that conveys a fresh, uncomplicated view of his subjects. Hofmann’s work often reflects the duality of life in almshouses: the harsh realities of poverty contrasted with a bright and cheerful aesthetic that flattered patrons, such as almshouse administrators.

The 1878 painting of the Berks County Almshouse exemplifies this approach. Using bright colors and precise lines, Hofmann depicted the institution from an elevated perspective. The central image is encircled by vignettes of various buildings on the grounds, presenting an idyllic view that glossed over the underlying struggles of its residents. Amidst the lively scene, subtle details, such as a man on crutches, reveal the complexity of life within the almshouse walls.

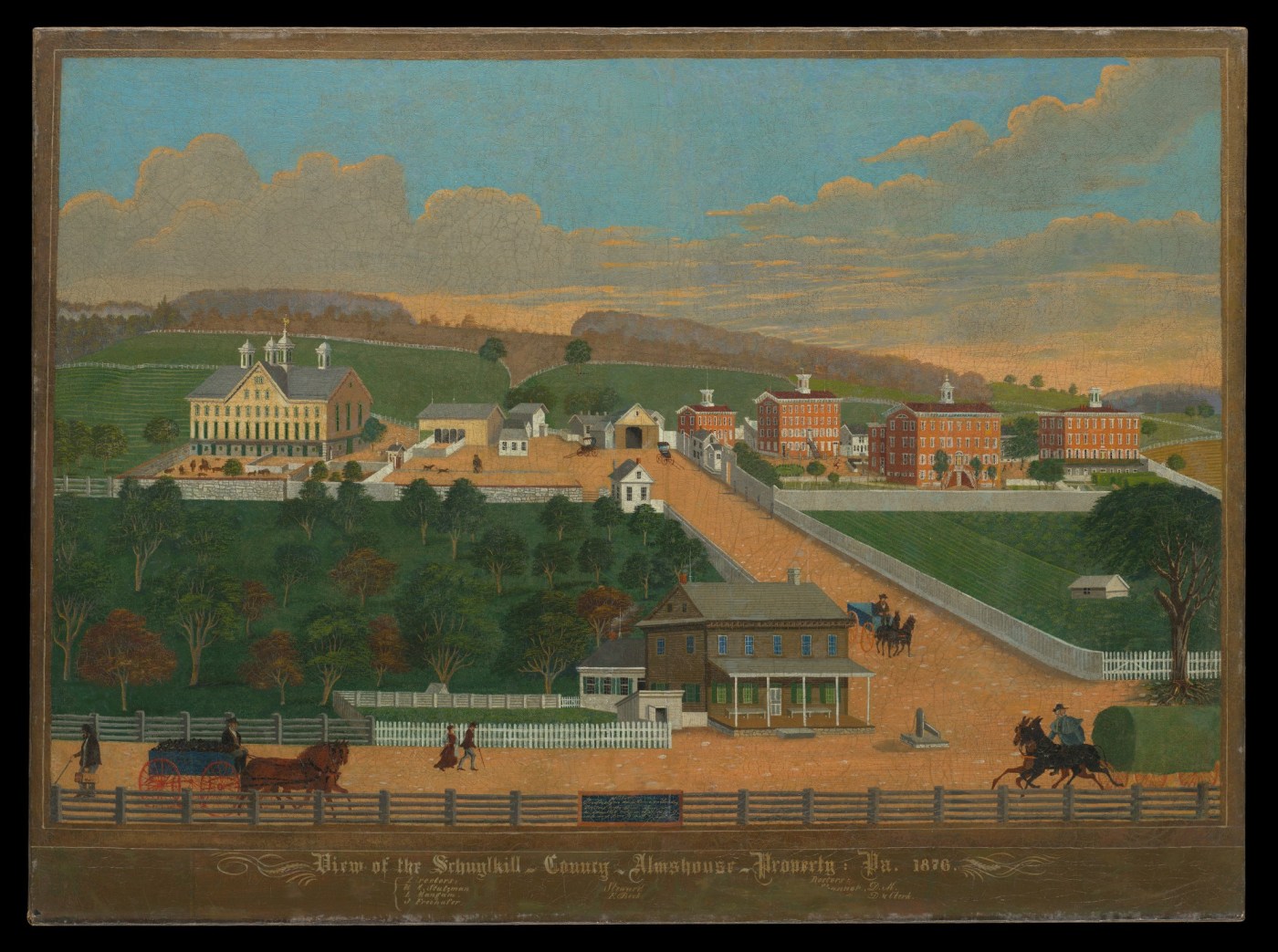

Hofmann also painted the Schuylkill County Almshouse in 1876, known today as Rest Haven. Similar to his previous works, this piece reflects a veneer of cheerfulness while hinting at the challenges faced by its inhabitants. Residents were often engaged in agricultural work, contributing to the institution while also depicting the harsh realities of their lives.

Charles C. Hofmann’s journey as an artist and a resident of almshouses highlights the intersection of art and societal issues. He not only captured the physical appearance of these institutions but also preserved their stories for future generations. His legacy serves as a poignant reminder of the resilience of the human spirit in the face of adversity, as well as the role of art in documenting and reflecting societal realities.