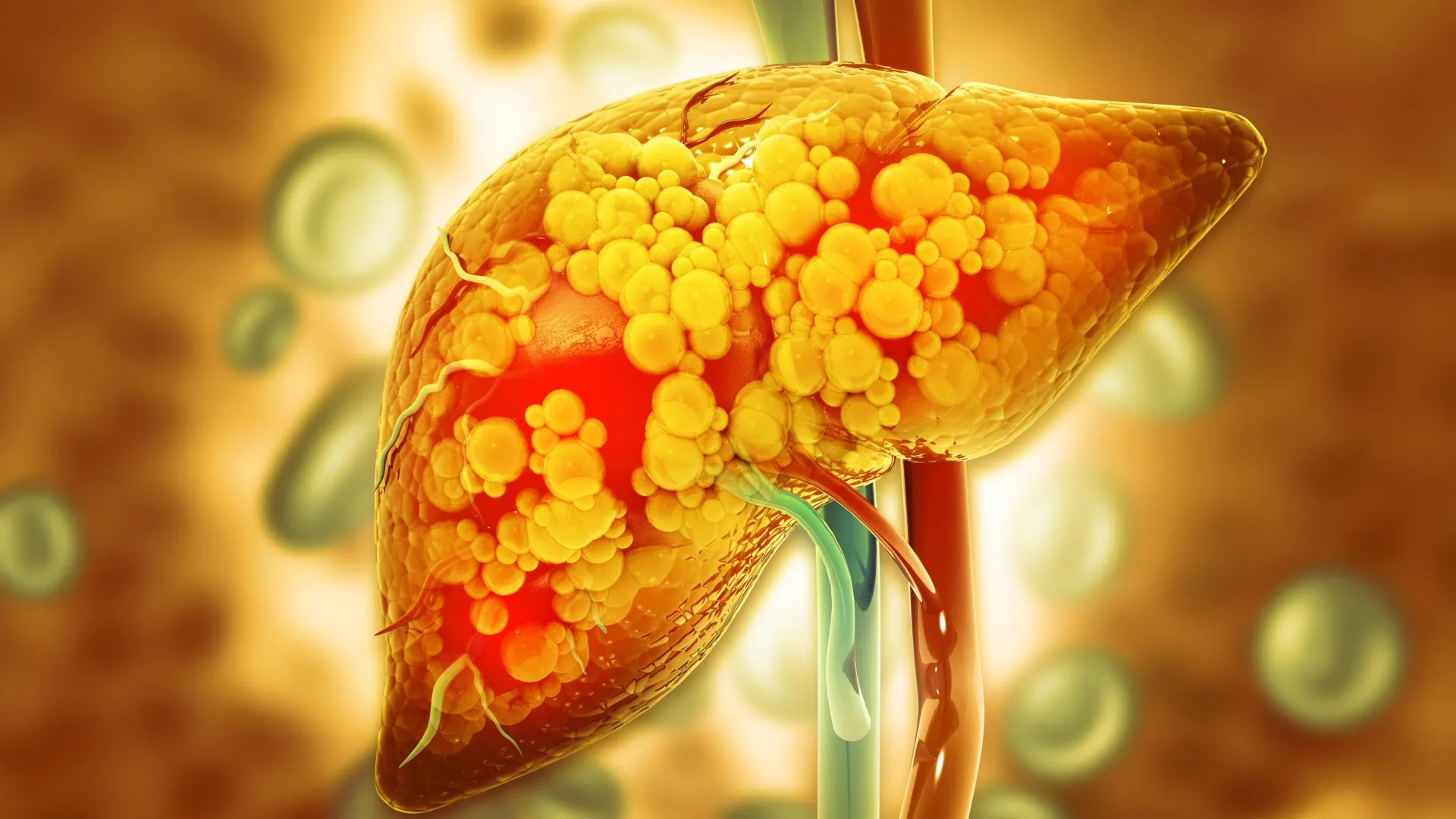

New research from the University of Oklahoma reveals that a compound produced by healthy gut bacteria may significantly mitigate the risk of liver disease in offspring. Published on February 8, 2026, the study highlights the potential of indole, a natural compound, in protecting against fatty liver disease in children whose mothers consume a high-fat, high-sugar diet during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Children exposed to poor maternal diets face a heightened risk of developing fatty liver disease, which can lead to serious health complications later in life. The study’s findings suggest that indole could act as a preventive measure. In experiments with mice, those whose mothers received indole showed remarkably lower rates of fatty liver disease as they matured.

Link Between Maternal Diet and Liver Health

Research indicates that a mother’s dietary choices during pregnancy can have lasting impacts on her child’s health. Pregnant and nursing mice were placed on a high-fat, high-sugar diet, simulating a typical Western diet. The researchers introduced indole to some of the subjects, examining its effects on their offspring.

According to Jed Friedman, Ph.D., director of the OU Health Harold Hamm Diabetes Center, “The prevalence of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in children is about 30% in those with obesity and around 10% in children without obesity.” He pointed out that this silent condition often goes undetected until a child exhibits liver-related symptoms, emphasizing the importance of early preventive strategies.

Investigating the Microbiome’s Role

Friedman, alongside Karen Jonscher, Ph.D., led the study, which focused on the gut microbiome’s influence on fatty liver disease development. The results showed that offspring born to mothers who received indole not only exhibited healthier livers but also maintained lower blood sugar levels and smaller fat cells, despite being exposed to an unhealthy diet later on.

Notably, the study demonstrated that the protective benefits were linked to the activation of a gut pathway involving the acyl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). The offspring that received indole showed no increase in harmful liver fats, while levels of beneficial fats rose significantly. A critical experiment involved transferring gut bacteria from protected mice to those that did not receive indole, further reinforcing the microbiome’s protective role.

Despite the promising results, the research has so far been conducted in animal models, meaning direct applications to human health are not yet available. The study suggests that improving the maternal microbiome could be a proactive approach to reducing the incidence of MASLD in children.

Currently, weight loss remains the only effective treatment for pediatric MASLD once established, with no approved medications available. Jonscher stated, “Anything we can do to improve the mother’s microbiome may help prevent the development of MASLD in the offspring,” highlighting the importance of maternal health in childhood liver disease prevention.

As research continues, findings from this study may pave the way for new strategies to combat childhood liver diseases, ultimately promoting healthier futures for children worldwide.