The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has made a groundbreaking discovery by detecting ultraviolet-fluorescent carbon monoxide in the protoplanetary debris disc surrounding the star HD 131488. This finding, reported by Cicero Lu of the Gemini Observatory and his co-authors, marks the first time such a phenomenon has been observed, shedding light on planetary formation theories.

Located approximately 500 light years away in the Upper Centaurus Lupus subgroup of the Centaurus constellation, HD 131488 is a young star, estimated to be around 15 million years old. Classified as an “Early A-type” star, it is both hotter and more massive than our Sun. Previous observations by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) revealed substantial amounts of “cold” carbon monoxide gas and dust situated 30-100 astronomical units (AU) from the star.

Recent preliminary infrared data from both the Gemini Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) indicated the presence of hot dust and solid-state features in the inner regions of the disc. Optical studies further suggested the existence of “hot atomic gas,” such as calcium and potassium, within the inner disc, providing intriguing insights into the disc’s composition and dynamics.

In February 2023, JWST focused on HD 131488 for approximately one hour. During this observation, it detected a small but significant quantity of “warm” carbon monoxide gas, amounting to roughly one hundred thousand times less than the cold gas in the outer disc. This warm gas was distributed between 0.5 AU and 10 AU from the star and exhibited critical temperature differences. The vibrational temperature, indicating the speed of atoms vibrating within the molecule, contrasted sharply with the rotational temperature, which reflects the spinning of molecules.

Typically, these two temperatures would align in a standard gas environment, achieving what is known as Local Thermal Equilibrium. However, in the case of HD 131488, the rotational temperature peaked at around 8,800K, while the vibrational temperature maxed out at only 450K. This discrepancy indicates that the molecules are not in thermal equilibrium, a condition that explains the observed fluorescence of the carbon monoxide.

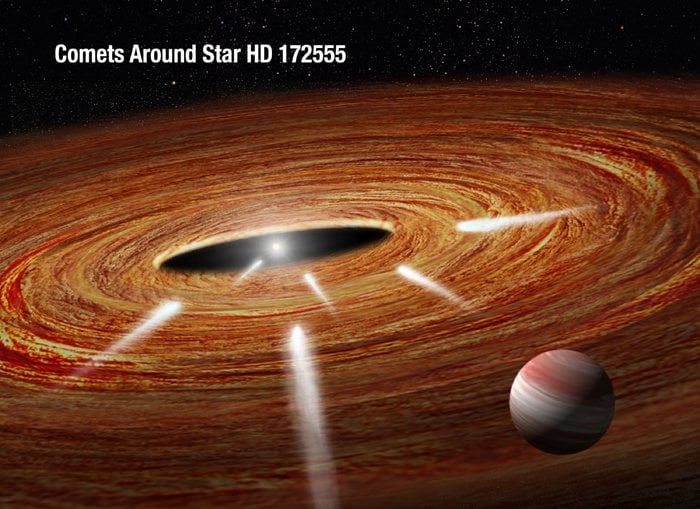

The study also revealed a notably high ratio of Carbon-12 to Carbon-13 within this environment, suggesting that dust grains might be blocking light within the sparse warm gas cloud. To emit the light pattern detected by JWST, carbon monoxide requires “collisional partners”—other molecules that interact with it. The research indicated that while hydrogen was less likely to be a partner, water vapor from disintegrating comets was a more plausible candidate.

This finding supports the hypothesis that the carbon monoxide-rich environment around HD 131488 is replenished by comets being destroyed, rather than being a remnant from the star’s formation. The implications for planetary formation are significant. The presence of ample carbon and oxygen in the “terrestrial zone” of the disc, coupled with a lack of hydrogen, suggests that any planets forming in this region would possess high metallicity, distinguishing them from hydrogen-rich primordial nebulae.

These discoveries underscore the capabilities of JWST, which has been producing a continuous stream of groundbreaking results since its launch. As research continues, more star systems like HD 131488 may provide further evidence to clarify the dynamics of carbon monoxide-rich debris discs and their role in planetary formation.