Advancements in understanding embryonic development emerged from a recent study conducted by biologists at Dartmouth College. Their research, detailed in EMBO Reports, reveals the mechanisms that allow embryos to transition from rapid cell division to the organization of specialized cells. This shift has significant implications for both developmental biology and potential applications in understanding human health issues.

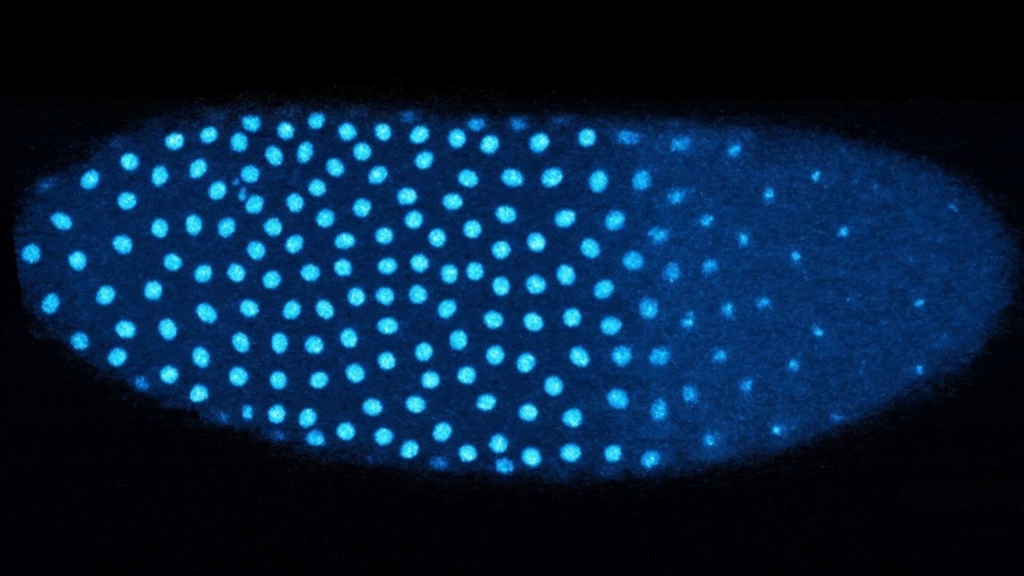

The study focused on the fruit fly, or Drosophila, a widely used model organism due to its transparent embryos, which facilitate detailed observation. Following fertilization, fruit fly embryos undergo approximately 13 rounds of rapid cell division, resulting in a dramatic increase in cell nuclei. The researchers discovered that the embryo’s ability to sense when to switch gears in development is linked to changes in the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio.

According to Amanda Amodeo, an assistant professor of biological sciences and senior author of the study, “The way that the DNA is packaged changes pretty dramatically in the very early embryo, as it goes from maternal control to transcribing its own genes.” This transition, she notes, is critical for understanding broader biological processes, including certain cancers and aging in humans.

Histone Switching: A Key Mechanism

The study identified a specific protein, histone H3.3, as crucial in this developmental transition. Histones are proteins that help package DNA within the nucleus, and they play different roles in gene expression. Prior to this research, the function of histones during early embryonic development was not fully understood.

Amodeo and her team revealed that when fruit fly embryos detect a high concentration of nuclei, they replace the standard histone H3 with the variant H3.3. This change is significant because H3.3 is associated with gene activation, suggesting that histones are not merely structural components but active players in gene expression during early development.

The study employed fluorescently tagged histones to track changes in the composition of histones as the embryos approached the critical 13th round of cell division. The results showed that as cell division progressed, the amount of H3 decreased while H3.3 increased. This switch is triggered by the embryo’s density of nuclei, highlighting the sophisticated mechanisms that govern cellular development.

Future Implications and Research Directions

The implications of this work extend beyond fruit flies. As Amodeo indicated, understanding the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and its relationship to histone changes could inform future studies on human health, particularly concerning conditions marked by disruptions in cellular organization.

Co-author Anusha Bhatt, a Guarini PhD student involved in the research, expressed interest in further exploring the role of H3.3 in genome activation in future studies. “I want to know where exactly in the genome H3.3 is being incorporated during those initial cycles, and what genes it’s activating,” she stated.

This research not only advances the understanding of embryonic development but also underscores the importance of fruit flies as a model for studying fundamental biological processes. As Amodeo noted, “Drosophila has, time and time again, helped researchers identify fundamental biological processes that end up being important for human and animal well-being, and we hope that’s also the case here.”

Two undergraduate students from Dartmouth, Madeleine Brown and Aurora Wackford, contributed to the paper, further illustrating the collaborative nature of this research. Brown, now a PhD student at Cornell University, and Wackford, currently studying at Dartmouth, have both played significant roles in the lab’s work.

The ongoing research at Dartmouth College continues to shed light on the complex processes governing development, with potential applications that could enhance our understanding of health and disease in humans.