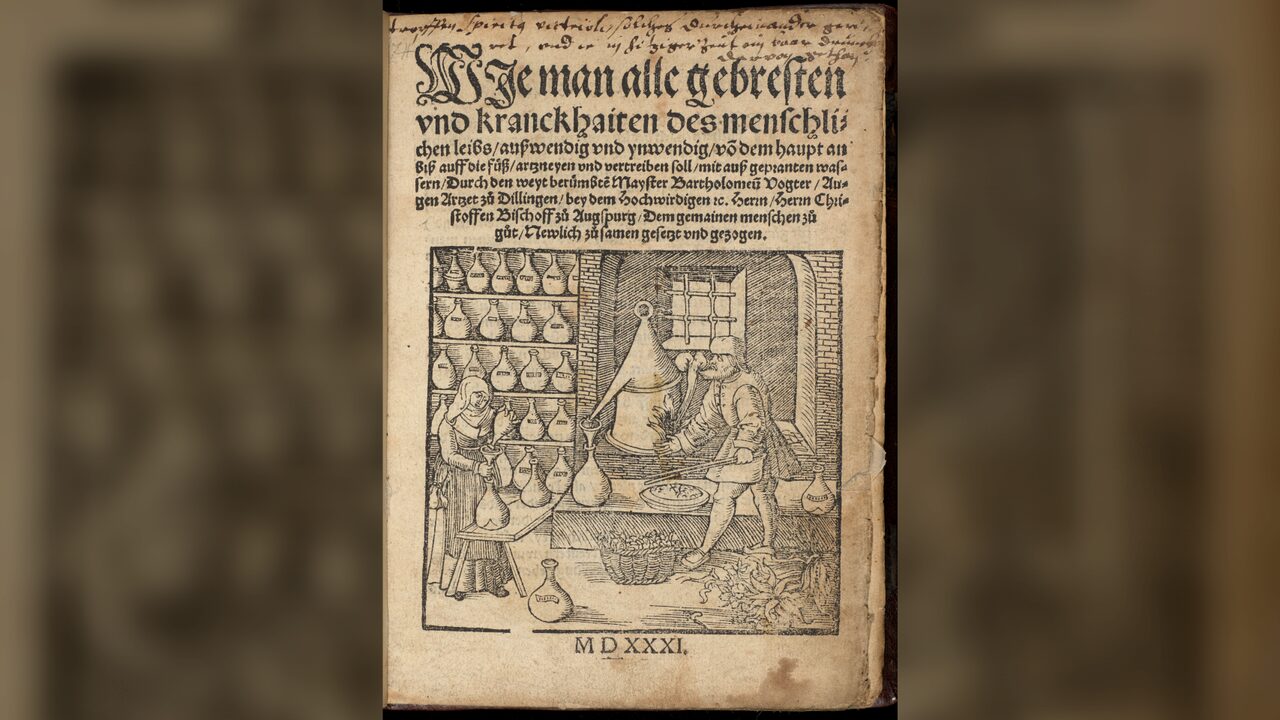

Researchers have made significant strides in understanding Renaissance-era medicine by analyzing chemical remnants found in two German medical manuals. These texts, published in 1531 by eye doctor Bartholomäus Vogtherr, contain recipes for treating various ailments, including hair loss and bad breath. The findings, published in the American Historical Review on November 19, reveal a fascinating glimpse into the practices of 16th-century folk medicine.

The manuals, titled “How to Cure and Expel All Afflictions and Illnesses of the Human Body” and “A Useful and Essential Little Book of Medicine for the Common Man,” quickly became popular among households seeking remedies. One copy, housed at the John Rylands Research Institute and Library at the University of Manchester, features numerous annotations and smudges, indicating that users actively tested and modified the recipes.

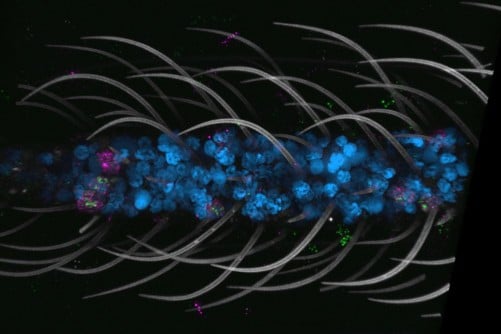

Researchers employed cutting-edge proteomics analysis to identify the proteins and peptides left on the pages of Vogtherr’s manual. According to study co-author Gleb Zilberstein, a biotechnology expert, “People always leave molecular traces on the pages of books and other documents when they come into contact with paper.” This includes substances from sweat, saliva, and environmental contaminants, which often remain invisible to the naked eye.

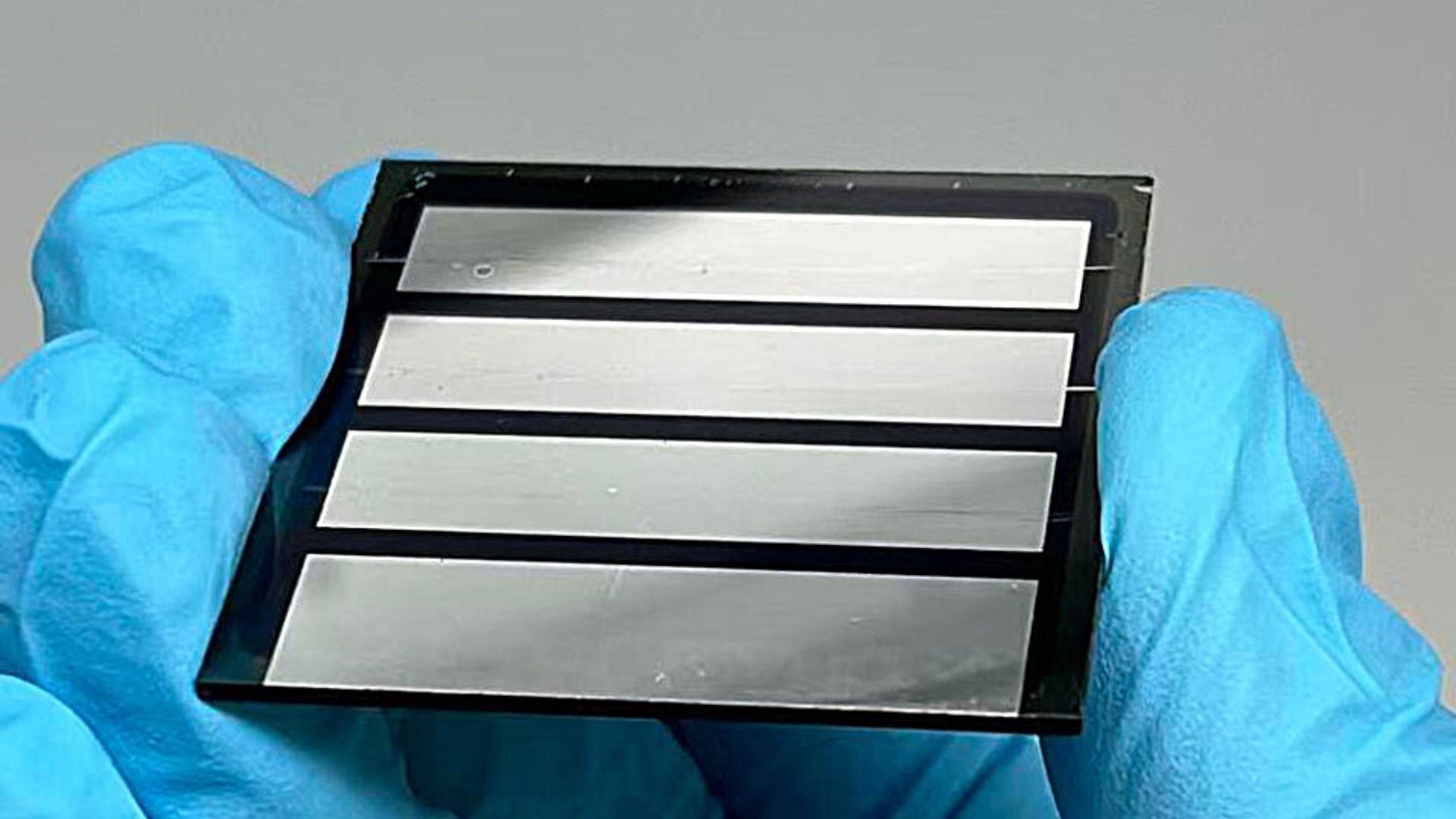

To collect these traces, the team utilized specially designed plastic diskettes to capture proteins from the paper. They then used mass spectrometry to analyze the amino acid chains, successfully sequencing 111 proteins from the manuals. While most of the proteins were linked to the manual’s users, several were associated with plants and animals mentioned in the recipes.

Among the intriguing discoveries, researchers found peptide traces from European beech, watercress, and rosemary adjacent to recipes aimed at curing hair loss. Notably, a trace of lipocalin, a protein found in human feces, was discovered next to a recipe recommending the use of excrement for washing the scalp to combat baldness.

Further analysis revealed a protein that could be linked to either tortoise shell or lizards. Historical texts indicate that tortoise shells were believed to alleviate edema, while pulverized lizard heads were touted as remedies for hair loss. This finding suggests that practitioners may have experimented with these ingredients for hair-care treatments.

The researchers also identified collagen peptides potentially connected to hippopotamus remains alongside recipes addressing oral and scalp ailments. During the Renaissance, hippopotamuses were often viewed as curiosities, with their teeth believed to cure baldness, severe dental issues, and even kidney stones. The presence of hippo protein might indicate that users of Vogtherr’s manual suffered from dental problems, as the relevant recipes were notably annotated.

Zilberstein emphasized that proteomics not only sheds light on the symptoms people faced when they consulted these manuals but also on the physical effects of the remedies they tried. The team’s innovative approach to studying ancient texts could lead to a deeper understanding of early modern household science.

Looking ahead, researchers plan to extend their work by examining other historical manuscripts and potentially identifying individual readers based on their proteomic data. This groundbreaking study opens a new chapter in the analysis of ancient medical practices and the remnants they left behind.